Ivers & Pond Boston -- Baby Grand Piano 71860

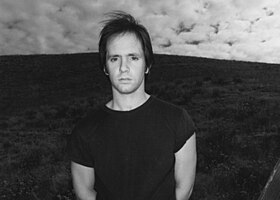

| Peter Ivers | |

|---|---|

| |

| Background data | |

| Nascency name | Peter Scott Rose |

| Born | (1946-09-20)September xx, 1946 Illinois, U.Due south. |

| Died | March iii, 1983(1983-03-03) (aged 36) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Genres |

|

| Occupation(s) | Musician, songwriter, composer, television personality, disc jockey |

Peter Scott Ivers (born Peter Scott Rose, September twenty, 1946 – March 3, 1983) was an American musician, singer, songwriter, and boob tube personality.[2] He was the host of the experimental music television evidence New Wave Theatre. Despite Ivers never having accomplished mainstream success, biographer Josh Frank has described him equally being connected by "a 2nd degree to every major pop culture event of the last 30 years."[3]

A native of Brookline, Massachusetts, Ivers' master musical instrument was the harmonica, and at a concert in 1968, Muddy Waters referred to him as "the greatest harp histrion alive."[iv] Afterward migrating to Los Angeles, Ivers was signed by Van Dyke Parks and Lenny Waronker to a $100,000 contract as a solo artist with Warner Bros. Records in the early 1970s. His albums Terminal Beloved (1974) and Peter Ivers (1976) sold poorly, but later on earned a cult post-obit.[v] He made his alive debut opening for the New York Dolls, and shared concert bills with such acts every bit Fleetwood Mac and John Cale.[6]

Ivers scored the 1977 David Lynch film Eraserhead and contributed both songwriting and vocals to the piece "In Sky (Lady in the Radiator Vocal)".[7] Later in his career, he wrote songs that were recorded past Diana Ross and the Pointer Sisters.[5] In 1983, Ivers was murdered under mysterious circumstances, and the crime remains unsolved.[8]

Life and career [edit]

Early life [edit]

Peter Ivers was built-in in Illinois on September xx, 1946, and spent the first ii years of his life in Chicago. His female parent Merle Rose was a homemaker; his male parent Jordan Rose was a medico, and became ill with lung cancer when Peter was ii years old. Soon after Jordan was diagnosed, the family relocated to Arizona in an try to help him recover. However, his health declined, and Jordan died in 1949.[9]

Merle quickly remarried to Paul Isenstein, a businessman from the Boston expanse. She didn't care for his concluding name, and picked the terminal proper name "Ivers" out of the telephone book as her new married name (Paul also took the last name, in an attempt to win her amore). Merle was a free spirit and doting mother, who exposed immature Peter to a wide diversity of music.[9]

From about age four, Peter was raised in Brookline, a suburb of Boston. He attended the Roxbury Latin School and then Harvard University, majoring in classical languages, simply chose a career in music. He started playing harmonica with the Boston-based band Street Choir.

Early career [edit]

Ivers embarked on a solo career in 1969 with the Epic release of his debut, Knight of the Blue Communion, featuring lyrics written by Tim Mayer and sung past Sri Lankan jazz diva Yolande Bavan). In 1971 he replaced Yolande with Asha Puthli on Take It Out On Me, his second album for Epic. The single from this second album, a cover of the Marvin Gaye number, "Ain't That Peculiar", backed by Ivers' original, "Clarence O' Day", was released and briefly entered the Top 100 Singles Billboard charts simply the album was shelved past Ballsy (only finally seeing the light of day in 2009).

In 1970, WNET and WGBH presented Jesus, A Passion Play for Americans, a play produced past Timothy Mayer, featuring his and Ivers' songs from Knight of the Blue Communion. Other important roles were played by Andreas Teuber, Asha Puthli, Steve Kaplan and Laura Esterman. The piece of work was broadcast every bit function of the WNET American Playhouse series. As a rock retelling of the story of Jesus, the work was a precursor to well-known examples of that genre, such equally Godspell and Jesus Christ Superstar.

In 1974, Peter signed with Warner Bros. Records, where he recorded two more albums.

Afterward career [edit]

In 1975, Ivers wrote the lyrics to the only compositions on the Threshold: The Blue Angels Experience film with vocals. Namely, these were; "Dawn: Eagle Phone call / The World Is Golden Too", "Noon: Rise Up Call / Wings / Blues Canticle" and "Night: Night Angels / She Won't Let Get". All were sung by Jim Connor.

In 1976, Ivers was asked past David Lynch to write a song for his movie, Eraserhead. Ivers penned "In Heaven (The Lady in the Radiator Song)", which became the most well-known limerick from the motion-picture show. He also scored the Ron Howard film G Theft Auto the following year. In 1979 he scored the fifth episode of the commencement season of B.J. and the Bear.

In 1977, Ivers produced a synth-pop/disco album for Roderick Falconer titled Victory in Rock City.

Ivers' best friend was Harvard classmate Douglas Kenney, founder of the National Lampoon. Ivers played "Cute Dreamer" on the harmonica at Kenney's funeral. Ivers was likewise a close friend of comedian John Belushi, who likewise preceded him in death.

In 1981, Ivers produced the Circus Mort EP featuring Swans front human being Michael Gira and advanced drummer Jonathan Kane. 1981 also found Ivers tapped by David Jove to host New Wave Theatre on Los Angeles Boob tube station KSCI which was shown irregularly as office of the weekend program Nighttime Flight on the fledgling United states of america Network. The program was a frantic cacophony of music, theater and comedy, lorded over by Ivers with his manic presentation. Using a method of filming known every bit "alive taped", the bear witness was the showtime opportunity for many alternative musicians[ disambiguation needed ] to receive nationwide exposure. Notable bands who appeared on the testify included The Angry Samoans, Expressionless Kennedys, 45 Grave, Fear, Suburban Lawns and The Plugz.

Also in 1981 Ivers experienced commercial success having written a song with John Lewis Parker that became an R&B top 10 hit for Phyllis Hyman called "Tin can't We Fall in Love Again?" Ivers formed a songwriting team with Franne Golde, and several of their compositions were picked upwards past successful artists, like "Niggling Boy Sugariness" recorded by The Pointer Sisters, "All We Really Need" recorded by Marty Balin, "Let's Go Up" recorded by Diana Ross and "Louisiana Dominicus Afternoon" and "Requite Me Your Heart Tonight"; both recorded by Kimiko Kasai. Ivers too appears in the pic Jekyll and Hyde...Together Again (1982) performing his song "Wham It" and had another composition "Light Up My Body" featured in the soundtrack.

In 1983, he performed on the Antilles Records release Swingrass '83.[10]

Death and investigation [edit]

On March 3, 1983, Peter Ivers was found bludgeoned to death with a hammer in his Los Angeles loft space apartment. The murderer was never identified.[iii]

In the hours following his death, LAPD officers sent to Ivers' dwelling failed to secure the scene, allowing many of Ivers' friends and acquaintances to traffic through the loft space. The scene was contaminated and officers even allowed David Jove to exit with the blood-stained blankets from Ivers' bed.[eleven]

Several of Ivers friends told biographer Josh Frank they suspected David Jove, with whom the musician had a sometimes contentious human relationship. Harold Ramis noted, "Equally I grew to know David a little improve, it but accumulated: all the clues and evidence but made me think he was capable of anything. I couldn't say with certainty that he'd washed annihilation only of all the people I knew, he was the 1 person I couldn't dominion out."[12] However, Derf Scratch (of the band Fearfulness) and several other members of the Los Angeles punk and new moving ridge scene maintained Jove's innocence.[13]

At the fourth dimension of his death, Ivers had been dating film executive Lucy Fisher for many years.[3] Nearly v weeks after the murder, Fisher paid for a private investigator named David Charbonneau to investigate the criminal offense. Charbonneau interviewed a number of people who knew Ivers just due to the botched initial investigation, lack of evidence and few witnesses, the renewed investigation came to nothing. Charbonneau stated: "I do not believe it was a intermission-in. I practise not believe it was merely someone off the street that Peter brought in because he was a squeamish guy that night and cruel asleep trusting them. I'g not ownership it."[14]

Legacy [edit]

Before long later Ivers' death, Lucy Fisher helped establish the Peter Ivers Visiting Creative person Programme at Harvard in the creative person's retentiveness.[15]

Josh Frank and Charlie Buckholtz wrote a volume almost Ivers' life, art and mysterious death, In Sky Everything Is Fine: The Unsolved Life of Peter Ivers and the Lost History of New Moving ridge Theatre, published by Simon & Schuster in 2008. On the basis of new information unearthed during the creation of the book, the Los Angeles Police force Department's common cold case section reopened their investigation into Ivers' decease.[3]

In 2013, The Guardian named Terminal Honey in their "101 Strangest Albums on Spotify" series. The newspaper noted that thirty years on, "Ivers' oddball leanings audio entirely contemporary. Those same arrangements that seemed so off-putting in 1974 experience rich and comfortable now, and the passing of time has leant Terminal Love a delicious hipster twang it couldn't possibly accept enjoyed equally a new release."[5] In a 2010 piece for NME, Danger Mouse listed Terminal Love as i of his favorite "underrated records."[16]

Discography [edit]

- Knight of the Blue Communion (Epic, 1969)

- Terminal Beloved (Warner Bros., 1974)

- Peter Ivers (Warner Bros., 1976; also known as Peter Peter Ivers)

Posthumous releases

- Nirvana Peter (Warner Bros., 1985; compilation of previous Warner recordings with bonus tracks)

- The Untold Stories (K2B2 Records, 2008)

- Take It Out on Me (recorded for Epic in 1971; released in 2009 by Wounded Bird Records)

- Becoming Peter Ivers (RVNG Intl., 2019)

Other appearances [edit]

- Buellgrass – Big Night at Ojai (K2B2 Records, 1983); released on CD every bit Buellgrass – Beyond the Tracks

- John Klemmer – Magic and Movement (Impulse!, 1974)

See also [edit]

- List of unsolved murders

References [edit]

- ^ a b Bloom, Madison (November 15, 2019). "Becoming Peter Ivers". Pitchfork.

- ^ "Peter Ivers". Movies & Television Dept. The New York Times. 2014. Archived from the original on 2014-10-06.

- ^ a b c d Sclafani, Tony (September 9, 2008). "Josh Frank on Peter Ivers, Murder & 'New Wave Theatre'". The Washington Post.

- ^ Frank & Buckholtz 2008, pp. 69–lxx.

- ^ a b c The Guardian article: "The 101 strangest records on Spotify: Peter Ivers – Terminal Love"

- ^ Frank & Buckholtz 2008, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Frank, Josh (August 6, 2008). "A Meeting of the Strange Minds: Peter Ivers, David Lynch and Devo". Retrieved December 31, 2017.

- ^ Wengrofsky, Jeffrey (September 9, 2008). "Following the Bunny Slippers Down the Rabbit Pigsty". Coilhouse Magazine.

- ^ a b Frank & Buckholtz 2008, pp. 21–23.

- ^ Allmusic review

- ^ Frank & Buckholtz 2008, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Frank & Buckholtz 2008, p. 202.

- ^ Frank & Buckholtz 2008, p. 204.

- ^ Frank & Buckholtz 2008, p. 206.

- ^ "About". Cerise Carriage Entertainment . Retrieved Dec 31, 2017.

- ^ NME commodity: "Danger Mouse and James Mercer – My Music"

Sources

- Frank, Josh; Buckholtz, Charlie (2008). In Heaven Everything Is Fine: The Unsolved Life of Peter Ivers and the Lost History of New Wave Theatre. Simon & Schuster. ISBN978-1-4165-5120-1.

External links [edit]

- Peter Ivers papers, circa 1965-1983, Houghton Library, Harvard University

- Peter Ivers at IMDb

- Josh Frank'south Peter Ivers site

- L.A. Weekly article

- Peter Ivers' last band he was in The Girlz of Zaetar on YouTube

cooneythujered1941.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peter_Ivers

0 Response to "Ivers & Pond Boston -- Baby Grand Piano 71860"

Post a Comment